ADVERTISEMENTS:

In this article we will discuss about the Morley-Minto Reforms and central government in India.

Indian Councils Act 1909 also introduced some changes in Central government in India. In this regard it was, however, clearly laid down that the Government of India must remain wholly responsible to the Parliament. But at the same time the government was keen that it should remain an autocracy till fully responsible system of government developed in the provinces.

It was now provided that though there would be no upper limit on the maximum strength of the Executive Council of the Governor-General, yet in its every branch there will be increasing association of Indians in their administration.

It was also provided that there will be three Indians in Governor-General’s Executive Council. Executive Council was, however, not made responsible to the Central Legislature but instead to the Secretary of State.

The legislature was given freedom to criticise the Executive Council, but a vote of no-confidence against the Council by the legislature had no meaning or effect on its existence in office. In effect the members of the Executive Council were not made responsible to it.

The Governor-General was authorised to issue ordinances, restore cuts and certify of all bills. At the Centre the Governor-General continued to enjoy a very strong and sound position. He had direct links with the Secretary of State, enjoyed great power of patronage and was the sole representative of the His Majesty Government in India.

Central government was made responsible to administer Chief Commissioners provinces of Delhi, Ajmer, Coorg, Andmans, etc. It was under direct charge of such subjects as Defence, Foreign Affairs, Indian States, Railways, Navigations, Posts and Telegraphs departments.

It also ensured that reserved subjects of the provinces were being administered efficiently and in accordance with the rules and regulations as framed by the British Parliament from time to time.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

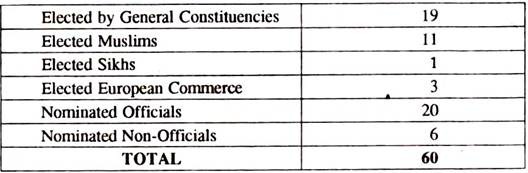

By the provisions of this Act Central legislature was made more democratic. It was made bicameral consisting of Council of State and Legislative Assembly. Maximum strength of Council of States was fixed at 60 out of which 34 were to be elected and remaining 26 to be nominated.

The composition of the Council on the whole was as follows:

The elected members of the Council of State were directly elected by the people on a very limited franchise basis and only those who paid income-tax or possessed good property were permitted to participate in the election. In addition, certain categories of other persons were also allowed to vote.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

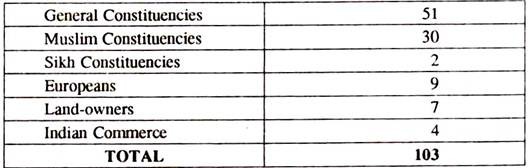

As regards Legislative Assembly, first such Assembly was to consist of 143 members of which 25 were officials. 15 nominated non-officials and remaining 103 were to be elected. There was reservation of seats for elected members as well.

The seat was distributed as follows:

In 1934, strength of the Legislative Assembly was further increased to 145 and representation was given by nomination to certain categories of persons including Anglo-Indians, Indian Christians and Associated Chamber of Commerce and Industries. In the case of Legislative Assembly, right to franchise was given to only few persons who paid municipal or income-tax or possessed some property.

Whereas normal life of the Assembly was kept at 3 years that of the Council of the State was kept at 5 years. Governor-General in his discretion could dissolve even the Upper House. The members of the Governor-General’s Executive Council could attend as well as address either House, though they had no right to vote.

Powers of the Central Legislature:

Central Legislature under the Montague-Chemlsford Scheme was a bicameral legislature. The authors of the reforms scheme were quite keen to maintain autocracy at the Centre till the provinces enjoyed full autonomy. The legislature was, however, given some more powers than what it enjoyed in the past.

It could enact laws for the whole country and could also repeal or amend any existing law except any parliamentary statute concerning India or Constitution of United Kingdom. In some cases previous sanction of the Governor-General was required for introducing a bill e.g., bills concerning public revenues of India, relations of the Government of India with foreign states, religious rites and usages of people of India, etc.

In addition, the Governor-General could also prevent discussion on any bill pending before any House of Legislature, if in his opinion such a measure was likely to disturb peace and tranquility of the country. He could also pass any measure which he felt was essential for nation’s peace.

He could also promulgate ordinances and return any measure passed by both the Houses of legislature for their reconsideration. He could also reserve any bill for the significance of His Majesty’s government. The members were, however, given the right to put interpellations, supplementary questions and move adjournment motions.

They had freedom of speech in both the chambers of legislature. They were given the right to vote on demands for expenditure except in certain cases where the expenditure was non-vote-able e.g., salaries and allowances of persons appointed by the Secretary of State in Council, interests and sinking fund charges on loans, etc.

While summing up the position of legislature at the Centre as set up under the Act, G -N. Singh opines that, “The Indian legislature was thus not only a non-sovereign law making body but it was also powerless before the executive.” In fact, central legislature had many limitations and the authors of Reforms did not make any secret of it.

Changes in the Home Government:

The Act introduced certain changes in the Home Government as well. The powers of the Secretary of State for India were somewhat reduced. A new office of the High Commissioner for India was created and some of the powers which were hitherto enjoyed by the Secretary of State in the past were now given to the High Commissioner.

Some of his powers were now delegated to the Governor-General in Council as well as the Governor in Council. Now it was not necessary that all legislative measures must be approved by the Secretary of State before introduction, which was a practice in the past.

Measures to be introduced in the provincial legislature were not to be referred to him. But in financial matters there was not much relaxation in control which remained very tight. All India Services continued to be controlled by the Secretary of State.

Changes were also made in Indian Council. It was provided that the Council of Secretary of State was not to consist of more than 12 or less than 8 members. It was also provided that at least half of these members should have served or resided in India for not less than 10 years at the time of appointment.

Secretary of State was empowered to give directions about the manner in which business of the Council should be transacted. Salary of the Secretary of State and members of his Council was also raised.

But even then he continued to have vast powers. His prior sanction was still needed with regard to provincial expenditure on reserved subjects, pay and allowances of All India service personnel, revision of permanent establishment in which recurring cost was more than 15 lakhs rupees, etc.

In order to have rigorous control over the Secretary of State, the Act provided that his salary will be paid from British exchequer. He was made accountable to British Parliament. He was given powers to make rules for the transaction of business of the India Council.

Indian States under the Act:

East India Company had followed policy of expansion in India which resulted in great discontentment among Indian princes, who rose in revolt in 1857. In that year when administration of India was transferred from the Company to the Crown it was made clear that there will be no further expansion of territories. Since then British government tried to establish herself as the patron of Indian princes.

In fact, Indian princes always looked towards Governor-General as the custodian of their rights and privileges. Whenever there was strain on the existing system, particularly by national movement, Indian princes came forward to the rescue of British rulers and lessened the pressure so that it could sustain itself as long as possibly it could.

British government, therefore, always ensured that it protected the interests of Indian princes. In order to consolidate their voice a Chamber of Princes was created but it was deliberately not allowed to discuss the internal affairs of any particular state or the actions of any individual ruler.

It was also said that the Viceroy will take advice of this Chamber in matters effecting their territories. It was also provided that whenever Governor-General thought it necessary he could convene a meeting for joint deliberations between the Council of State and Council of Indian Princes or between the representatives of each body.

In the words of A.B. Keith, “The Report recognised to the full the importance of the position of the States and the effect which the Reform Scheme must have on their interests.”

Civil Services in India:

The steel frame of British administration in India was civil service. Civil servants were neither civil nor servants nor Indians. They were stiff necked unconcerned officers planted in India by British Parliament to ensure that whatever system was introduced that was fully operated by them to the advantage of Britain.

Their ability and success very much depended upon their capacity to save the system from outside pressures.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

They were to see that the system worked well and did not bow and also external pressures were not so forceful as to lead the system in the direction of their liking. It was, therefore, left to the Secretary of State to decide about the method of their recruitment, fixation of their pay scales and ensuring their rights and privileges.

Their dismissal could only be by the Secretary of State, who could even reinstate a dismissed employee. It was also provided that a Public Service Commission will be appointed in India on the pattern of Civil Service Commission in United Kingdom.

The Secretary of State could delegate rule making power of civil service personnel to the Governor-General. He was also empowered to appoint a Public Service Commission consisting of not more than five members, including a chairman.

The civil servants were to hold office during the pleasure of Secretary of State. He was empowered to appoint Indian civil service personnel domiciled in India and also Auditor General of India.

Provision was also made for the appointment of a Commissioner who was to see how far India was ready for having responsible government and to which extent progress had been made in such fields as spread of education and working of system of government, as introduced by this Act.